Illustration by Elliot Burr

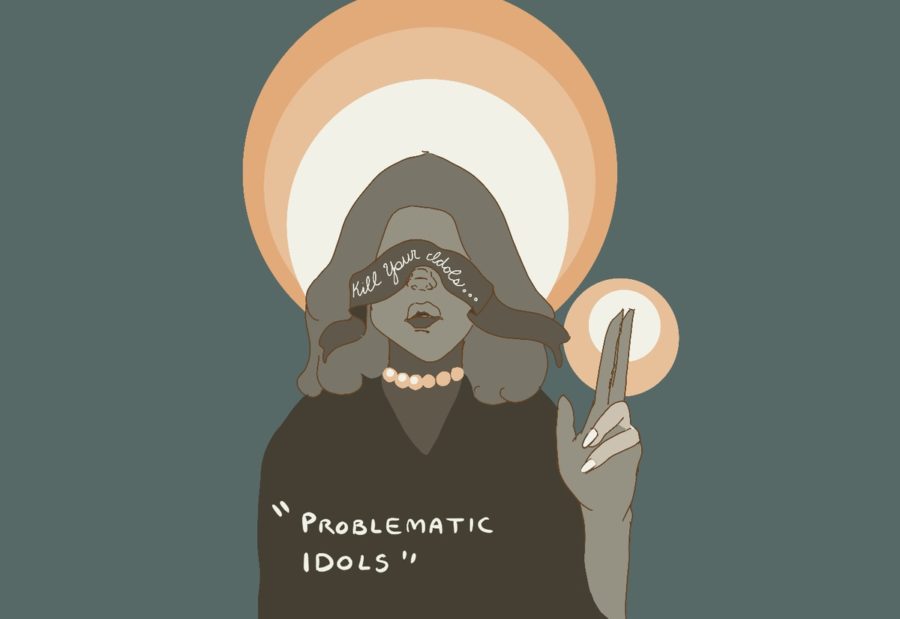

My 16-year-old self used to listen to Morrissey and The Smiths on repeat. With all their lyrics memorized, I was obsessed. Effortlessly consuming their art for hours. Daily karaoke sessions of “Sudehead” and “First of the Gang to Die.” Blown away by pictures of young Morrissey reading Oscar Wilde, thoroughly convinced he was the most impressive man alive. My teenage passion wore off quickly when I learned about Morrissey’s discourse. My heart sunk in my chest when I read his political views and how he spoke about minorities. I felt sick that I supported such a bigot, even for a second. However, I still loved his music. Just like that, I was faced with a tale as old as time. Should I disregard this and continue to listen to my favorite songs, or should I not support someone that has been so offensive? My teenage mind could not handle this moral outrage; I could not bear to stand by it. This decision, however, cost me the daily doses of joy that this art provided me. Many of those who appreciate art, in any form, experience this conflict. No matter the medium, it seems like a problematic artist can always be found.

From musicians to writers to filmmakers, the public has been exposed to their art as well as their behaviors. Artists’ lifestyles are routinely portrayed and romanticized in their artistic endeavors. Writers Charles Bukowski and Ernest Hemingway are the epitome of the glorification of alcoholism. “On Drinking,” a book by Bukowski published 25 years after his passing, is inspired by the addiction the poet faced throughout his life, including some famously known incidents, such as when Bukowski was visibly drunk during a French national television program airing live. Hemingway was not too far behind, as he continually bragged about being able to “drink hells any amount of whiskey without getting drunk.” Hemingway’s alcoholism was so influential that 61 years after his passing a book called “To Have and Have Another” was written about his drinking habits. Does this constant display of addiction influence their audience? Is it even on them to be role models and display healthy behaviors?

Now onto film, Quentin Tarantino’s art is violent while continuously over-sexualizing women and perpetually depending on the male gaze. Tarantino displays masculinity or accomplishment as dependent on violence, and the most inspiring characters always seem to be those that can win in every fight, such as the Bridge in “Kill Bill” or Cliff in “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.” Furthermore, the movies diminish great actresses, such as Sharon Tate, to a character with a small amount of lines that revolves around others, such as her husband. What is the public that cherishes their work ought to do? Simply cut ties with their favorite forms of art? Continue to support these problematic artists?

Should an artist’s works have value on its own no matter what the artist has done? Morally questionable figures have always made major contributions to art, following the well-known rhetoric of the great artist who turns out to be a terrible person. To continue to treat the art the same is quite appealing. It should not matter who made the work, merely the reaction one has to the work.

Some might believe we are supposed to value artistic expression by itself, assuming that art is from a different domain, apart from the artist’s life, causing the art to not be influenced by the artist’s lifestyle, opinions or behavior, regarding art as something standing on its own. Art is, like all aspects of life, a product of existing systems of power. The perception of art is shaped by who society celebrates and who it silences. Art does not exist on its own, as it is part of the world and the systems of power within it. Every medium of art caters to a market shaped by these same systems of power. Art is affected by various outside sources. The artists do not separate themselves from their work. The choices made by the public regarding their art consumption yield influence to the artist. By consuming the art, you are supporting the artist. This is not a strict moral matter; you are not a bad person for liking The Smiths’ songs, but it is merely a matter of tracing cause and effect. Throughout this long and tiring process of figuring out if an ounce of joy is worth more than what I stand for, I came to a satisfactory personal conclusion. There will always be great unproblematic artists just as much as there are great problematic artists. I thoroughly believe I should not need to give up my musical joy just because one artist did not live up to my moral standards. All that is left to do is find a singer I like just as much and who does not make me want to write a story about my moral conflict when listening to them. So many smaller artists wait for us just to choose to appreciate their art for once. A multitude of musicians, writers and filmmakers incorporate social justice in their art, and I from now on, will choose to support them.