In the center of the stage, assistant stage manager Austin Scott is on his hands and knees playing a gecko.

He’s out there for a while, circling an actor, repeating her lines after her. While some roles in this show have understudies, this one doesn’t. Leaving Scott to fill in when the original actor can’t make it to rehearsals.

Once the scene wraps and they move onto the next, Scott returns to the back of the stage, sweat percolating on his forehead. He gives a sharp look to another assistant stage manager, Nicole Berrios-Parga who offers him a sympathetic one in return.

“It’s hot under those lights,” he said.

“This was not a part of the job description,” she said jokingly.

When in fact, it is part of the job description as stage managers act as the show’s most trusted apprentice.

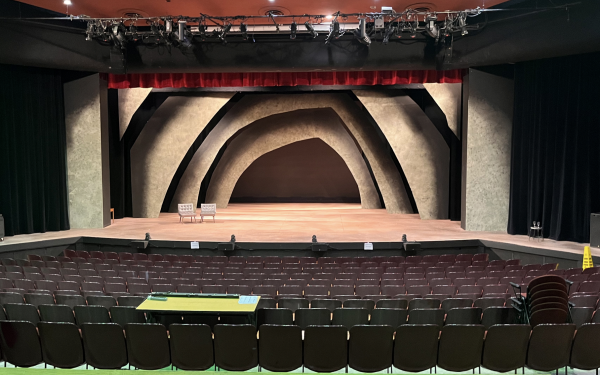

Theater has many moving parts. The lights help convey emotion, the sound builds the atmosphere and the set immerses the audiences into the story. The actors on stage memorize their lines, cues and directorial notes to bring forth a memorable performance to the audience. All of theater’s components work separately to cultivate an experience for the audience. One missed cue and the illusion is gone.

Beyond the curtains of E. Turner Stump Theatre in Kent State’s performing arts building is the backstage. There is a gray marked-up floor, high ceilings with lights that seem to go on for forever and miscellaneous props and set decorating pieces. While the site is nothing too spectacular, it holds the life of the show. Beyond the curtain is where it all comes together.

The stage management crew of the show “Passage” whisper together as the actors rehearse on stage. The show, written by Christopher Chen, tells a story about two fictional countries in a tense relationship because of one colonizing the other. While the show’s topic is heavy and is reminiscent of real-world events, there is an air of lightheartedness behind the scenes. Natural relationships form amongst the cast and crew as they work together in rehearsals up until its run from September 28 to October 1.

The quiet conversations consist of inside jokes, task delegations and answering questions posed by the actors. Berrios-Parga and Scott stand on opposite sides of the stage in view of each other, copying dance moves as if they were each other’s shadows. Each of them has their own responsibilities behind the stage, for instance, Scott oversees the prop weapons. As they all have their own jobs, they can still make time to look up what time Meijer closes for a curious actor.

While they relish in the idle moments, they are always ready to take note of any change in production made by the director, which happens often.

The primary stage manager acts as the hub of communication across all the design departments and the director. They also call the actors into rehearsals, cue the lights and sound and facilitate changes within the show.

For this production, Noah Johnson, senior theater management major is the primary manager who oversees the others. Upon first impression, he appears shy, only speaking a few words at a time. But in rehearsals, he comes alive, with his voice booming around the theatre as he calls out directions. For a job that is responsible for overseeing all the moving parts of the show, a commanding presence is helpful.

“It can be daunting at times, but once you get up to that level, it’s sort of an honor to be trusted with such a big responsibility,” Johnson said.

Theater attracts people from different walks of life who are enamored by the art of live performances.

Scott, a senior theater management major, started off as a performer. That was until the allure of having a hand in making a production come together called his name.

“I was originally an actor, but decided that like, with all the imperfections that theater has, being in the acting settings, you can’t really change anything,” Scott said. “So, with going into management sides of things, we tend to make things better for multiple different people.”

Because these productions only have a little over a month to put a show together before opening night, stage managers are required to be at every rehearsal, which could run up to six days of the week. Whereas actors only have to show up for scenes they are rehearsing for that day. In addition to regular rehearsals, stage managers arrive an hour early, leave an hour late and have weekly production meetings. Stage managers usually average around 50 hours per week on their respective shows, Scott explained.

As participation in the semester’s show is required for the major and professors also work on these productions, they are understanding when it comes to schoolwork.

Loraine Getty, freshman theater stage management major, found the production schedule and workload to be a big adjustment.

“There’s a lot of hard work and you really have to be committed to it,” Getty said. “…I don’t really get a full day to myself, except Saturday off-days.”

Since every stage manager has different areas of focus throughout the performance, it’s

important for them to all be quick to embrace change for the sake of the show.

“Just being able to adapt and pick up those changes really fast for the show to run smoothly the way it should be,” Scott said. “It’s kind of challenging, but when you have a great team, like this team, we’re able to do it really fast.”

The key to ensuring everyone keeps up with the fast-paced environment: communication and community.

While most of the stage managers opted for behind-the scenes work because they loved the creative process away from the spotlight, Scott said that he wished people knew the human effort put behind their favorite productions.

“But without all the work with all the spectacle, the lighting, the sound, the direction, it all is run by people,” Scott said. “Even though technology is advancing so much that some of these things aren’t run by people anymore. There is still live human involvement behind the stage to make what you see come to life.”

At the end of a show’s run, the set is cleaned up, with no trace of it ever existing, and the stage prepares to welcome the next production. Despite the amount of work stage managers pour into their productions, there is a bitter sweetness to every show’s end. Every moving part of the production, after spending hours with each other over the course of weeks, forms a bond over the experience they helped create.

“Passage” ends with a monologue asking the audience to reflect on their perspective of the show. Everyone will walk away with their own conclusion that is formed by their own past experiences and understandings of life. Scott is walking away with the family he formed through the show and a sense of achievement.

All that matters at the end of the day is what the crew and the audience leave with.

“It’s a good thing to see what you’ve been working on, so long and hard, has been completed,” Scott said. “… But the result of like, what the audience feels, what the actors feel, like just the completion of is like the end goal for us.”

reilly • Oct 26, 2023 at 10:03 pm

Best article ive ever read