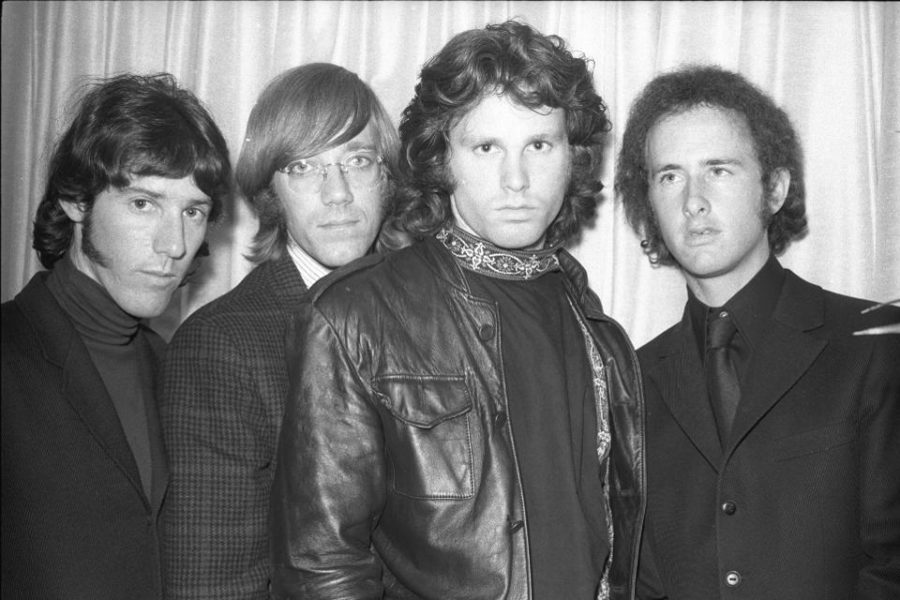

In the rock canon, there aren’t many bands like The Doors. Simultaneously underground and mainstream at the same time, they’ve certainly left their mark in the rock genre and numerous sub-genres, like punk and gothic rock for example. However, I’m still conflicted about my opinions on them as I love parts of them yet l0athe other aspects surrounding the legacy of The Doors.

The Doors started in 1965 after singer Jim Morrison ran into his former college buddy, Ray Manzarek on the beach in Venice, CA. Even before they ever released any singles or albums, they were pegged as the rebellious poets of the L.A. scene. They were fascinating yet magical and oh so mysterious. Most of this was tied to Morrison, as he was seen as prettier, sexier, dangerous and more clever than any other rockstar before and during his time. The band was also extremely eclectic with their influences and references. The whole of the band was obsessed with poetry and philosophy, particularly Aldous Huxley, William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud and many others. Morrison would also pick up performance elements from the experimental Living Theater novel by Julian Beck.

Their musical influences were also diverse and all over the place. Drummer John Densmore had a flair for Bossa Nova, which influenced songs like “Break on through (to the other side).” Guitarist Robby Krieger has classical guitar training, which can be found in the flamenco solo and backing on “Spanish Caravan.” Manzarek, whose organ made up for the band’s lack of a bass player, is probably the signature of The Doors sound. At times darkly hypnotic, like a midnight carnival ride and at other times funky yet warm, like something from a Ray Charles b-side or soft and brooding, like a Motown torch single.

Critics at the time lauded this experimentation and darkly brooding subject matter Morrison surrounded himself in. They also often wrote about Doors albums like they were collections of poetry. Take this review of the first doors album from Crawdaddy! in 1967 by Paul Williams:

“The Doors is an album of magnitude. Thanks to the calm surefootedness of the group, the producer, the record company, there are no flaws…This record is too good to be ‘explained,’ note by note. Jim obviously didn’t give that much of a damn about the girl in this case [in the song “Soul Kitchen”] so something else must have been bothering him. The intensity of that plea could not have been faked. And this leads us to the really stunning revelation that sexual desire is merely a particular instance of some more far-reaching grand dissatisfaction.”

This was pretty true to the reaction critics had to The Doors’ early albums, praise as well with fascination about the band itself. The Doors were essentially the ultimate pop critic and music nerd band; poppy yet still experimental with their style and had interesting lyrics and instrumentation. The main difference was that Morrison had the looks of Greek myths and allegories which drew a separate audience of teenage girls, purely gawking at the classical beauty and deep siren calls of the lead singer. He was more raw and sexual than Mick Jagger and even raunchier and more rebellious than Elvis, who was the pinnacle of teenage sex symbolism. Adonis, the human lover of Aphrodite, would be the most common comparison to Morrison’s primal and magnetic looks.

As much as they disliked this aspect of their fans, they kept chugging along with more praise from critics and fans. They amped up the theatrics with their third record, Waiting for the Sun, however, the media attention surrounding Morrison’s annoying and illegal on-stage actions marked a downward shift in the band’s acclaim.

When discussing this album upon initial release in 1968, Rolling Stone writer Jim Miller wasn’t impressed:

“Listening to the new Doors’ album, Waiting For The Sun, reminded me of Zappa and also how good the first Doors album was; yet after a year and a half of Jim Morrison’s posturing one might logically hope for some sort of musical growth, and if the new record isn’t really terrible, it isn’t particularly exciting either.”

The fans were starting to expect and even anticipate Morrison’s outbursts which began to take a toll on the entire band. The band had almost become entirely focused around Morrison and his artistic vision, leading to their most critically panned record, The Soft Parade. Alec Dubro summed it up with his review of the album for Rolling Stone in 1969 saying, “The Soft Parade is worse than infuriating, it’s sad. It’s sad because one of the most potentially moving forces in rock has allowed itself to degenerate.”

It was sort of depressing at the time, these beacons of interesting rock music had become sort of weak and corny, much like how Elvis was at the time. However, after Morrison’s numerous legal battles, they pulled up their bootstraps and stripped it down for their final two records; “Morrison Hotel” and “L.A Woman.” These records, which adopted a more stripped down, testosterone covered blues-rock, were admired though not entirely loved by critics. Robert Meltzer, writing for Rolling Stone, had a very enthusiastic opinion on “L.A Woman:”

“You can kick me in the ass for saying this (I don’t mind): this is The Doors’ greatest album and (including their first) the best album so far this year. A landmark worthy of dancing in the streets.”

The praise would ultimately take on a whole new connotation three months later when Morrison mysteriously died soaking in booze and bathwater like a prune in July of 1971. In life, he was a normal counterculture rockstar; in death, especially young and pretty, Morrison became a legend, a myth, something otherworldly and more force of nature than human being.

The Doors’ legacy is where the divisions, including my own, bubble to the surface. The true span of the legacy of The Doors doesn’t truly show up until the ‘80s and ‘90s when teenagers brought back both the ‘50s and ‘60s and made them cool and interesting again. Writer and boozehound Lester Bangs reflected on the legacy of both the group and Morrison in 1980, a decade after he torched their album “Morrison Hotel” for Rolling Stone.

“We seem to be in the midst of a full-scale Doors Revival…Perhaps a more apposite question, though, might be can you imagine being a teenager in the 1980’s and having absolutely no culture you could call your own? …And this is not just Sixties nostalgia–it’s a simple matter of listening to them side by side and noting the relative lack of passion, expansiveness and commitment in even the best of today’s groups. There is a halfheartedness, a tentativeness and perhaps worst of all a tendency to hide behind irony that is after all perfectly reflective of the time but doesn’t do much to endear these pretenders to the throne.”

This isn’t exclusive to The Doors and the youth of the ‘80s and ‘90s either; we can see this occurring today with our modern youth and their obsession with the culture of the ‘90s. However, The Doors and Morrison, mostly due to his death obsession and early demise, had been launched into this idea of what the movements of the ‘60s and ’70s were supposed to mean. The ‘60s were supposed to be this giant decade where everything changed and the youth revolted, questioned authority and revolutionized the American idea of just about everything. However, what got lost in the shuffle when the youth of the ‘80s and ‘90s rediscovered the ‘60s was that most of those revolutionary figures either died due to their own excess, assassination, or had become cogs in the money-making machine once the counterculture had been adopted as a way to make money.

Morrison was an example of that, however, due to his rebellious actions and mystic aura and tendencies, he’s become a symbol rather than a person. The myth of Morrison is summed up with the title of the Rolling Stone article from 1981, following the release of a popular Morrison biography “No One Here Gets out Alive”: “He’s Hot, He’s Sexy and He’s Dead.” Even alive, those were the appeals of Morrison’s persona, the classic gothic mixture of attraction, sexual rawness and how that allures to death.

The issue that I see is while that is true of Jim Morrison, that was mostly his press or performing image; behind the scenes, he was a drunk bad poet who was a serial cheater and drug addict. He’s not the only one who’s like this, even from the ‘60s, but he’s been deified and for that I point the blame to director Oliver Stone and his 1991 film about the band, “The Doors.”

Stone, known for his tendencies towards conspiracy theories, portrayed Morrison as being controlled by the spirit of a dead Native American shaman who he saw die on the highway as a child, a story Morrison often told but nobody could verify. Stone ran with this tale and made him a folkloric or nature figure of death and destruction.

Despite the other members of The Doors disapproving of this film and its portrayal of Morrison, they’ve also played into this version of Jim Morrison whenever they’re discussing him. They made him out to be some sort of artistic groundbreaker, which is a subjective term, but he simply wasn’t that. Morrison was more so the prototype of the know-it-all types who hide their toxic qualities behind their brains.

He was a talented writer and singer, but you can see the patterns and annoying misogyny once you actually sit down and read his lyrics. He likes to borrow Rimbaud and William Blake’s apocalyptic primalistic images. He likes reptiles, booze, death, girls and himself. That’s more my issue with The Doors and Jim Morrison; they’re not concepts or these earth shattering cultural events. They were a pretty good experimental rock band with a hot yet smart lead singer who died due to his own excess.

Featured image courtesy of The Doors.