“Suicide if you ever try to let go I’m sad, I know, yeah / I’m sad, I know, yeah.”

-XXXTentacion, “SAD!”

“You can see the void in my eyes I know you know I’m lying when I say that I’m fine.”

-nothing,nowhere., “deadbeat valentine”

Welcome to the newest installment of Nina’s Bite-Sized Thesis! If you missed the last installment, or if you just need a refresher on your emo rap knowledge, you can read my previous blog post here.

The theme for today’s blog post is one that is nearest and dearest to the heart of emo rap and also incredibly significant to American life and culture: mental health. The genre as a whole is characterized by an intense focus on sadness, despair and suicidal thoughts, often accompanied by talk of risky behaviors like drug abuse and suicidal ideation as responses to mental health problems. Because these themes are defining aspects of the genre, rather than occasional occurrences, it is more logical to hypothesize that emo rap songs are popular because they feature mental health, rather than in spite of this fact.

One of the major concerns about emo rap, as with emo, rap and rock ‘n’ roll music before it, is whether engaging with this music is a legitimate cause for concern. This is undoubtedly a complicated issue and one with many factors to consider. While individuals who are struggling with their mental health or issues like drug abuse may be drawn to emo rap because they identify with those challenges, they may also engage with the music for other reasons, such as forming relationships with their peers and aesthetic appreciation. The reasons that a person engages with emo rap music is as important to determining whether the experience will positively or negatively impact their mental health as the content of the music itself.

Many critics highlight emo rappers’ honest discussions of mental health as one aspect of the genre that has the potential for positive impact. Lil Peep in particular was often credited with serving as a role model within the genre for adolescents struggling with mental health issues because he used his music as a vehicle to express rather than obscure his own issues. Authenticity is a major concern within the genre: artists want fans to know that their experiences are genuine (nobody likes a clout chaser), but as the genre gains more popularity, it becomes harder to tell if artists are merely capitalizing on the demand for “sad rap” content. In his article, “Should You Listen to XXXTentacion’s ‘17’?,” Andrew Matson expresses his concern about a possible “trendification of suicide,” meaning that emo rap artists use their music to promote sadness as an aesthetic more than they try to promote productive discussions about mental health. The more controversial an artist’s performance of sadness, the harder it can be for critics and listeners to determine how to interpret it.

The full extent of emo rap’s impact will likely not be revealed for a long time, but the widespread reach of the genre is no longer in question. Tom Breihan, in his profile of now-deceased emo rapper Juice WRLD, considers SoundCloud rap “quite possibly the de facto sound of teenage America in 2018.” Breihan also states that the genre is populated by “a new generation of male rappers embracing their own victimhood,” blaming others for causing the undesirable feelings that so frequently appear in their music. As an example of this phenomenon, Breihan refers to “Lucid Dreams,” stating that Juice WRLD’s top-ten single is “an oddly pretty song about taking pills and contemplating your own death, all because some girl did you wrong.” Breihan argues that, while emo rappers like Juice WRLD are sincere in the intensity of the emotions they express, that should not excuse the fact that the content resulting from feeling those emotions can be questionable and set a poor example for listeners.

The response from many emo rappers also demonstrates that whatever catharsis is achieved from creating emo rap does not completely salve the emotions that the genre expresses. Vermont-based emo rapper nothing,nowhere., who has said in interviews that creating music provides an outlet for the worst emotions he faces, canceled his 2018 summer tour the night before it was supposed to begin, explaining via Twitter that he had been battling severe anxiety and depression and had decided that he needed to seek professional help. In early 2019, Lil Uzi Vert announced that he would take a break from making music, citing a desire to be “normal,” which implies that one cannot feel normal while making music that requires him to engage with negative emotions and dissect negative events in his life. Emo rap artists live in the same culture as their fans, in the same environment that enabled their music to become popular, and their feelings are not immune, either.

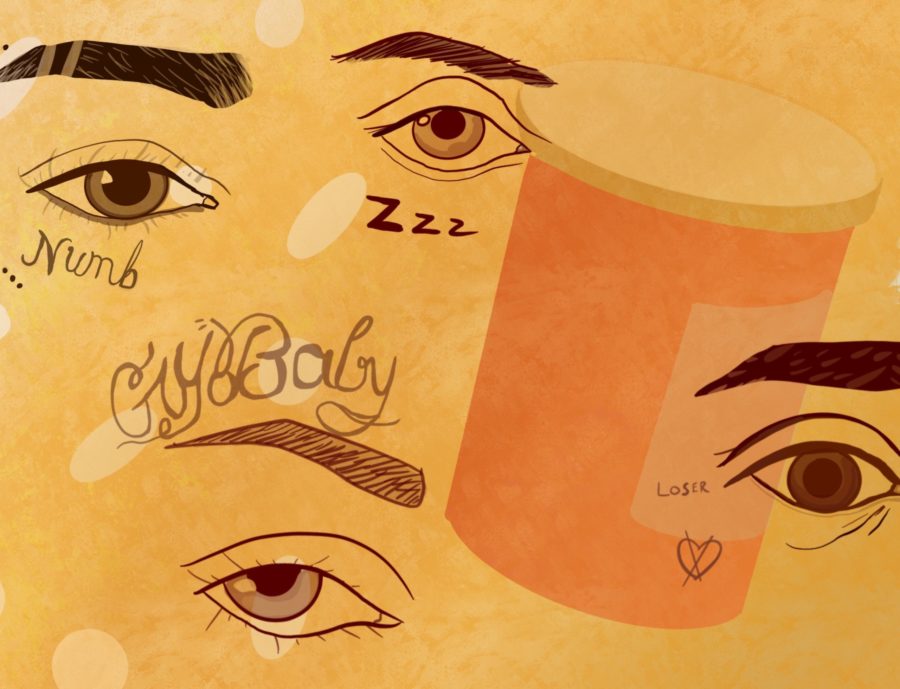

Just as the emotional content of emo rap music is not new to American culture, neither is another definitive hallmark of the genre, drug use and abuse. In her book “The Age of Anxiety,” author Andrea Tone charts the rise of Miltown (meprobamate), an anti-anxiety drug that was approved for sale by the Food and Drug Administration in 1955. (I didn’t include Tone’s book on my suggested reading list because of its length, but if you have the time, it’s worth a read.) Miltown was an incredibly popular drug by both the standards of its own time and by those of today; within a year of its debut, approximately one in twenty Americans had tried it, a greater ratio than that of any drug that has been introduced on the American market. According to Tone, Miltown arrived into a society that was “preoccupied with anxiety and committed to its containment.” A similar connection between anxiety and the need for its control can be observed in the upward trend in prescriptions for benzodiazepines in modern America. If you’re interested in learning more about the connection between emo rap and drug use, there will be much more where that came from in the next installment.

That concludes this second blog post — thanks for reading! The suggested songs for this post were selected because of their connection to mental health issues and the feelings of malaise and despair expressed within them; feel free to listen to them in any order. The articles below will provide a bit more insight into how some emo rap artists approach mental health in their music, for better or worse. Stay home, stay safe and I’ll meet you back here for the next one!

Suggested listening:

“SAD!,” XXXTentacion

“hopes up,” nothing,nowhere. (feat. Dashboard Confessional)

“nineteen,” Lil Peep

Suggested reading:

Tom Breihan, “Juice WRLD Turns SoundCloud Rap into Toxic Emo-Pop.”

Lindsay Zoladz, “All the Young Sadboys: XXXTentacion, Lil Peep, and the Future of Emo.”

Nina is the copy desk chief for The Burr. She can be contacted via email at [email protected] or on Instagram @ninaepwrites.