Photos by Anastasia Lawrence

The rock, due to its simplistic and solid form, has become a ubiquitous symbol of Kent State as a whole. Since its inception in the 1930s, it has become a canvas for a variety of groups to express themselves to the campus and community. Originally placed on E. Main Street, it was later permanently relocated to the famous Hilltop Drive location. It has become a tradition to visit or write on the rock for any Kent State student; its no-holds-bar nature has made it a timeless icon of the university. However, the extremely lax rules of what can go on the rock created the possibility of something offensive or threatening being written on it.

The first message did not appear out of a void, rather it covered up a previous message of “Say Their Names,” a recent phrase attached to the Black Lives Matter Movement. Nevertheless, it was still shocking to the Kent community, and on August 28, the first racist message appeared on the rock. Initially, what the racist message specifically said was not disclosed. Later, photos of the rock covered with the phrase “White Lives Matter” spread on social media and were then harvested by media outlets. The incident incited outrage within the community, specifically within the Black student population.

Tayjua Hines, president of Kent’s Black United Students, was particularly outraged. “My first reaction was that I laughed because the racism was starting already especially considering what was previously on the rock,” she said. Hines along with a couple of students quickly worked to repaint the rock with a portrait of Queen Tiye, the Queen of Egypt from 1390 to 1353 BC. Tiera Moore, president of the undergraduate student government, was also present for the first repainting.

In an interview with Krista S. Kanto for The Record-Courier, Moore expressed her upset at the timing of the racist message’s appearance on campus. “I’m trying to think of all our freshmen but especially our African-American freshmen who just got here. It’s a really bad way to start the semester,” she said. “I’m disappointed that someone would do this so early on. It sets a negative tone for the semester.”

This would not be the last time a racist message would be painted over an image of empowerment.

It has happened three times over the course of a month. After the second message appeared, which transformed “Hate has no home here” to the threatening “Blacks have no home here,” people began to increasingly get angrier and disgusted. Hines quickly decided she wanted to effect change.

“The second time [a racist message was posted on the rock] I was pissed, because they were playing tit for tat and were just being disrespectful and cowardly(…),” Hines said. “As the president of BUS, I wanted the Black community to come together and paint the rock again; the second time I wanted action steps from the university to address the situation i.e. a denouncement statement.”

Some students, like Hines and Moore,decided to repaint the rock to dispose of the disgusting messages. Makenna Brumbaugh, a junior criminology major, was one who was deeply upset by the messages left on the rock. “My boyfriend had texted me saying the rock was repainted with the hate speech of ‘Blacks have no home here.’ Me and two of my roommates immediately went to go cover up the awful words that were written on the rock.”

Unfortunately, despite her respectful intentions, she received backlash online. Brumbaugh was not expecting the backlash her post would bring. “I never responded to anyone or really liked anyone’s comments/replies even if they were good. I had to realize that on social media the way people perceived what we did was going to be taken the way they wanted it to be taken, and I wouldn’t be able to change their minds about my heart or my intentions on the issue at hand.”

The backlash however was understandable, as some saw it as an example of performative activism: focusing the spotlight on a safer version of the revolutionary actions that are often performed by underrepresented groups but ignored by media attention. This could be seen as a microaggression, a non-physical interaction which comes off as aggressive, from the media to the Black students of Kent.

The majority of student reactions to the constant back and forth on the rock was revulsion and rage. This was aimed both at the anonymous culprits constantly painting these messages and the university itself. Shockingly, the university took a surprisingly long amount of time to release a statement on the matter. Quickly, after releasing a statement decrying the messages, the university then shifted talks to removing the rock all together after the messages kept popping up. This seemed to be a superficial band-aid on an open sore of a bigger issue.

Hines also stated how frivolous the rock removal statement seemed. Hines said, “The words on the rock, the rock is not the problem, it’s that they felt emboldened to do it multiple times. It also exposes the racism, micro and macro aggressions and neglect that Black students, staff and faculty have been facing here at Kent and Kent State since we’ve been here.”

Kent‘s BUS released a public list of demands. The BUS called for the university to implement security methods and notifications to prevent further actions and inform students if they do happen. The university quickly met with them and assured that their demands would be met as soon as possible. However, unsatisfied students converged on social media where the steps towards change began to intensify and spread.

After repainting the rock seemed to do little, two students decided more striking actions would catch the attention of the university more.

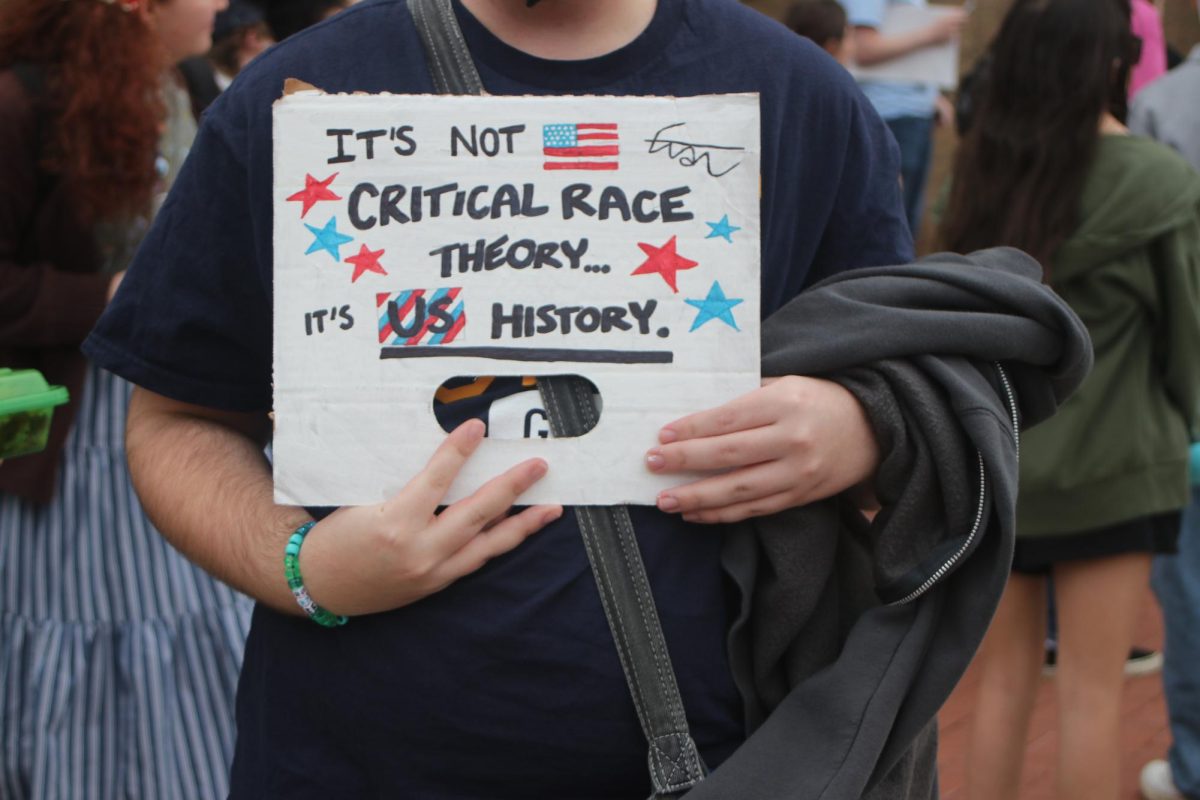

Tory Wenson and Kamalenn Gillespie, with assistance from the Kent BUS, organized two days of protesting to advocate against the issue of racism on campus. The images of students marching all across the campus and speaking their perspectives, advanced across social media and gained more supporters on the side of the protestors.

Todd Diacon, president of Kent State, did not show up until the second day of protests. In the videos on Twitter, he is seen listening to, speaking with and marching with the students, which immensely picked up the mantle on behalf of the university.

Kent’s BUS organized another march, entitled the March for Unity, following the protests. President Diacon along with Dr. Lamar Hylton, vice president of student affairs, and Kent Police Chiefs Nicholas Shearer and Dean Tondiglia took countless questions about how the university will go about making their students feel safe, both on the campus and within the city of Kent as well. Assistant editor Chris Ramos covered the march for KentWired. In his piece, Ramos chronicles the changes requested by the students that the university enabled.

“Pressed by [Greek Council Vice President Patrick] Ferguson and students, Diacon agreed to compile the university’s action steps into a mass email sent to students by the end of the day (…) In addition to security measures to the rock, Hylton concluded the march by stating that the university is establishing a rock policy and will explore possibilities in the student code of conduct.”

The responses and activity taken by the university shows a positive progression forward for the protection of the students. The actions of the students from the very beginning of these are really what has kept this awful injustice in the spotlight. They have also kept the focus on the major issues at hand since this is not just about a rock. Hines conveyed how racism is something that is deeply ingrained within the education system and how tapping into that is what is going to solve it. She explained, “To address racism properly you first have to talk about the racism that’s present and ingrained in the education system. After that, acknowledging its roots and moving forward with action plans to make systemic change to the infrastructure of our institution.”

The university, despite their initial lack of action, has quickly picked up their slack and started addressing the issues students have brought to them. They have also kept the majority of the spotlight on the students’ activism, keeping a backseat guiding role and making sure they are going to continue to assist the students.

This is only the start of change. If this year has shown anything, it has shown that people will no longer be stepping back when it comes to getting the change they crave. It also shows the determination to keep issues in the light long when the media no longer cares. The hope for many is that the issue of the rock will end up leading to change to make Black students feel more comfortable and safe on Kent’s campuses, both now and in the future.