Cover photo: The Lordstown Complex operated by GM from 1966 to 2019, before being sold to electric auto manufacturer Lordstown Motors. Photo by Wyatt Loy.

Growing up, kids are often told about the expectation to keep a five day, 40-hour work week at one job until they are 65 — but that standard of work is quickly fading away. Side hustles and second jobs on the weekends are necessary for some people to stay afloat, and data shows young adults spend less than a year and a half at any one job. The work standards of old were fought for and maintained by labor organizers, but in the last 70 years, that fight turned upside down.

“It’s been a very difficult time for labor unions to organize,” Visiting Scholar at the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor John Russo says. “The American labor movement in the modern era really changed, but there’s always been an enormous anti-union sense in the country.”

The early days of organizing

The modern day labor movement started in 1935 with the National Labor Relations Act. People working in the private and industrial sectors finally had the opportunity to come together and bargain for higher pay, better working conditions and fewer hours.

Throughout the 30s and 40s, workers went on strike frequently and utilized many different tactics:

- Jurisdictional strikes, which assert a union members’ right to a particular job

- Mass picketing, which are huge strikes with overwhelming numbers

- Wildcat strikes, or strikes that are not authorized or approved by union leadership

This all changed in 1947 with the Taft-Hartley Act, which “changed the situation in terms of organizing power in ways that companies would begin taking advantage of,” Russo says. The act outlawed many of the tactics labor organizations use, including each of the above strikes and then some.

“At the same time, in the 1960s, we saw the rise of public sector unions becoming extremely important,” Russo says. “An enormous number of women were entering the labor force, because they were largely in the service industries that hadn’t been very effectively organized.”

Women did some labor organizing in the garment industry during those years, Russo says, but it never became as large or impactful as when women moved to public sector jobs like education, healthcare and government.

Let’s talk about Lordstown

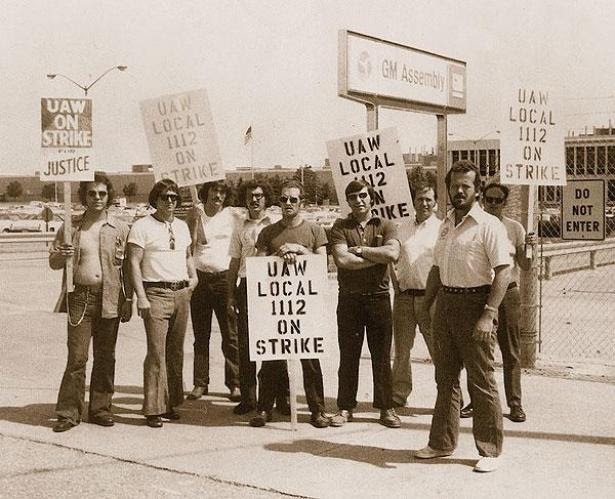

United Auto Workers on strike in Lordstown, 1974. Image courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

The Lordstown Complex was an automobile factory owned by General Motors and located in Lordstown, Ohio, just a 45-minute drive from Kent. It served as a jobs mecca for the people in the area, employing more than 14,000 people even at the time of its closing.

Labor organizing has always been central to Lordstown’s history. Growing worker grievances and union infighting in the early 70s sparked a massive strike in 1972 that lasted 22 days. If you want to experience some of what the workers at Lordstown did on the production line, Russo offers this exercise:

Pick up a pen and open a notebook to a blank page. Write something for 35 seconds, then stop for five seconds. Then write again for 35 seconds, followed by another five-second break. Repeat this process and find that you become increasingly frustrated with the repetitiveness and futility of the exercise.

This, Russo explains, was what factory workers experienced on a much larger scale for hours at a time.

“Now, I want you to think about what it was like at Lordstown, when they were pushing 100 cars an hour down the assembly line,” Russo says. “That was the rate that they had to get, and you wonder why people started rebelling against it.”

The Lordstown strike sparked a national movement dubbed “Lordstown syndrome.” Workers at other auto plants would engage in wildcat walkouts, sabotage and general civil disobedience. In response, many of the factories in Northeast Ohio like the Delphi auto parts plant, moved to different parts of the country or overseas altogether.

Where to next?

Looking toward the future, chances of success in labor organizing appear slim. Policymakers in both parties are loath to pass legislation expanding the right to unionize, while companies use existing legal structures to prevent further organization and bargaining.

Ohio, as of 2020, has an employed population of 4.8 million according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. 13.2% are union members, while 14.2% are represented by unions. Private sector union membership in the broader United States dropped from about 12.5 million in 1983 to about 7.5 million in 2015.

With ever-dwindling numbers and the legislative odds stacked against them, how are labor organizations supposed to move forward? Russo talks about unionism as having two models: economic and political unionism. The former is what organizers used traditionally, while the latter is a more contemporary model.

“Economic unionism is the type of unionism you develop to improve wages, hours and working conditions by going through individual collective bargaining,” Russo says. “The other type of union is political unionism, and they get all their stuff done through politics.

“You can see there’s a move right now in this country, the Fight for $15. The idea is to build a large group of people that will support a political policy. The point of it is if you can’t bargain for improvements in wages, hours and working conditions, then you have to fight for it in a different way.”

Recently, Democrats in Congress tried to pass the Protect the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would expand workers’ ability to form unions and restrict employers’ abilities to fight unionization before it starts. The PRO Act could not pass the Senate in regular order, even with a Democratic trifecta in the federal government.

Russo says this is part of a pattern he has seen in the past of the inability for lawmakers to adequately provide for workers rights, and grassroots organizing likely holds the key to progress.

“I think that if we’re moving more and more toward a type of political unionism, that’s going to join up with a lot of the types of local community organizing that’s going on,” Russo says. “So you basically develop a large cohort of people who can push the political parties toward change that will improve the rights of working people in general.

“And in this country, there’s a whole set of social issues that could be addressed, certainly in your lifetime. You’re going to have the type of resentment that’s building in younger people that were told ‘Don’t worry, things are going to be okay.’ They’re not.”